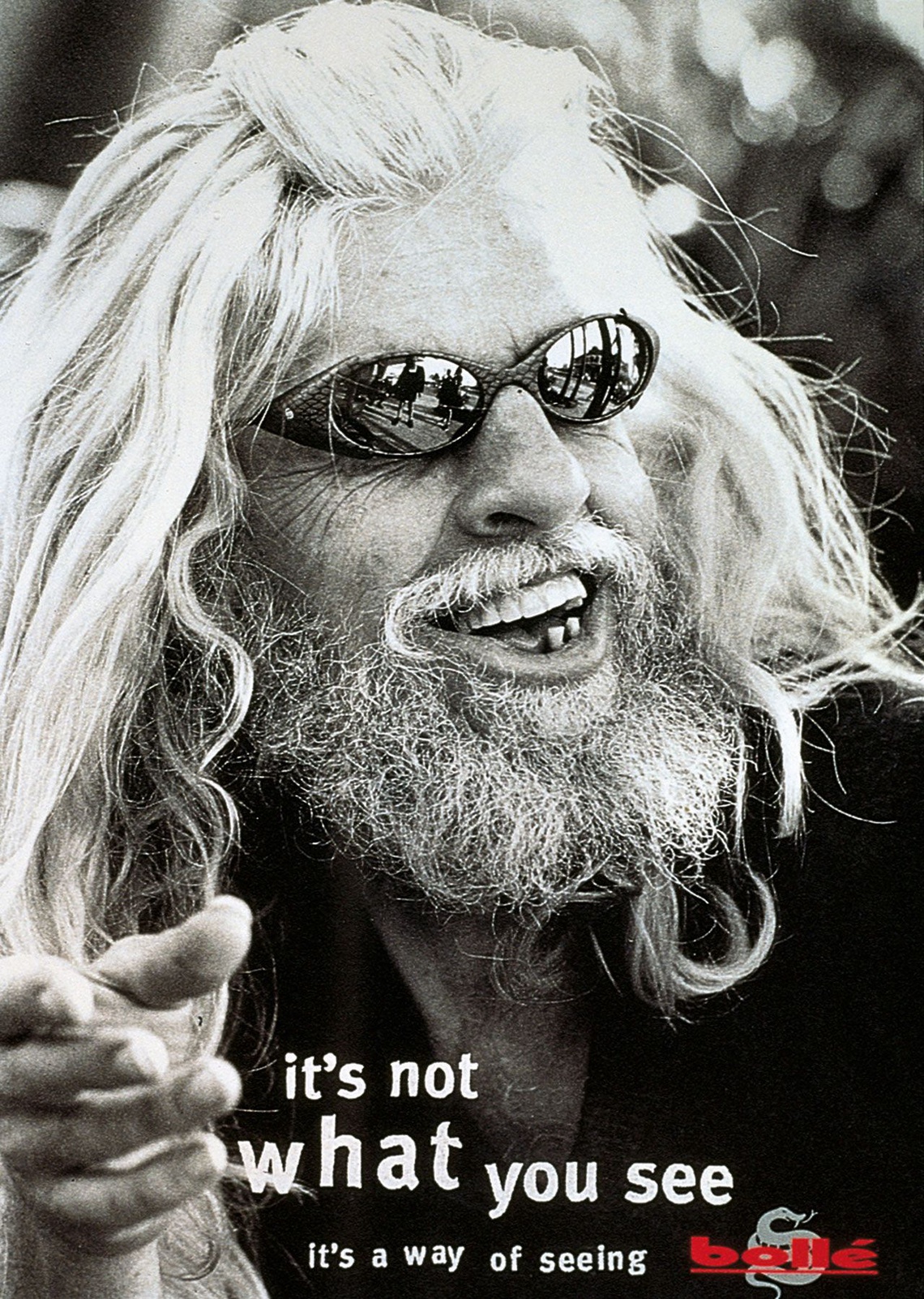

The natural tendency is not to follow new ideas.Creative mastermind Edward de Bono is the author of innumerable books. He has acted as adviser to heads of state, artists and musicians, advertising agencies, and multinational corporations. He runs the World Centre of New Thinking in his native country of Malta. Hermann Vaske spoke to the man who coined the term “lateral thinking” about the most valuable asset in the creative industries: ideas.

L.A.: Mr. de Bono, what is an idea?

Edward de Bono: An idea is a putting together of different elements, different pieces of experience to form something new, either to carry out a function or to form a description, but it’s the putting together of separate pieces which have been experienced.

L.A.: What kind of people have ideas?

Edward de Bono: Well, there are different people who have ideas. Some people need to have ideas because their profession demands ideas. If you are in advertising, you need to have ideas, and in product design you need to have ideas. Artists are a little different, I’ll come back to artists later. And there are people who are motivated to have ideas and they have excitement in having an idea. They want to have ideas and they have ideas, even if no one listens to them. So you could say there are people who are motivated to have ideas, and some people have a motivation in having ideas.

L.A.: Does everybody have ideas?

Edward de Bono: Let’s start at the beginning. When you are an infant, a baby, you have to have ideas. You only progress in the world by forming ideas. Ideas of how your mother treats you, ideas of what happens when you cry long enough … someone gives you some food or something. So a child grows up forming ideas all the time. They are new ideas for that child but not new ideas in terms of the world. Once you have a picture of the world, and if you experience that same world every day, then you may not have any further ideas, any new ideas. And everything is now routine, a recognized situation, a recognized way of doing it, an existing idea.

L.A.: So a housewife, to use a cliché, baking a cake can have ideas?

Edward de Bono: Well, you don’t need to. I mean, exceptionally you might, for instance, but two weeks ago I invented a new way of cooking an omelet. Now, that’s not strictly necessary – we have existing ways of cooking an omelet. This is, of course, a much better way. But that is an idea dealing with a situation where there is already a routine solution, a routine idea.

L.A.: What was your idea for cooking the omelet?

Edward de Bono: You fill an omelet with scrambled eggs. You make your omelet, you make your scrambled eggs; you leave them running and fill the omelet with the scrambled eggs – very simple. And it works very well.

L.A.: Damien Hirst once said to an interviewer who had said, “I could have done that,” about one of Hirst’s art pieces: “Yes, but you didn’t.”

Edward de Bono: Well, this is a very important point. Any valuable creative idea is always – I repeat: always – totally logical in hindsight. The danger of that is people say, once you have the idea, it’s perfectly logical, therefore you did not need creativity. This arises from the way the brain forms patterns as symmetric patterns, and once you come down a side pattern it’s obvious. I’ll give you another example: suppose we have a tree and there’s an ant on the trunk of the tree. What are the chances of that ant getting to one particular leaf? Where at every branch point the chances diminish by one over the number of branches; in the average tree, the chance of getting there is one in eight thousand. Ok, now, let’s put the ant on that leaf. What are the chances of that ant getting to the trunk of the tree? One in one. There are no false branches on the way back.

L.A.: Would you say the difference between the so-called ideas people and the non-ideas people is that the ideas people just do it whereas the other ones talk about it, think about it, but don’t do it.

Edward de Bono: Well, there are always ideas people who do things and ideas people who don’t do things. The ability to do things is partly personality, partly self-confidence, and so on. So you may have ideas and do nothing about them, and you may not have ideas and do a lot about them, or you may have so many ideas that you cannot deal with every one of them. And the history of ideas shows that if you want an idea to succeed, you should be single-minded and determined on that single idea, then you make it happen. If you have too many ideas, you can’t follow them all.

L.A.: So an idea not being executed, would you say that’s a non-idea, collecting dust in the cupboard?

Edward de Bono: No, it’s an idea which is in the potential stage and it may be rediscovered, may be executed, many years later. And our ideas apply to anything. I’ll give you a very simple example: in China at the moment there is a shortage of a hundred million women. The cause for this, I think, is that, thirty years ago, the government introduced a one-child policy. Now what happens is, in Chinese culture, the family likes to have a boy to look after them in their old age because the girl marries and goes to look after the family of the husband. So, somehow, the girls disappear – they may be killed, they may be sold, they may be adopted. The result: a shortage of a hundred million women. Now, if they had asked me for my advice, I would have given them a better idea, which is every family can have as many children as they like until they have a boy. After that, you stop having children. Result: equal boys and equal girls because, at the moment of conception, it’s roughly equal; you are not killing anyone, so it will stay equal – equal boys, equal girls. Every family has a chance to have a boy, you get a declining population, because in this system you get on average two children per family and for replacement you need 2.3. So you will get equal boys, equal girls, and every family has a chance to have a boy and a declining population. A much better idea. But what I’m saying is that this is an idea just as much as any other idea. An idea of how to do things; how to organize things is an idea.

L.A.: Is ideas-solving a problem, or is this only one facet like the manifestations of our thoughts?

Edward de Bono: Well, you see, our word “problem” is used in many different ways. It’s used when there is a difficulty. But it’s also used when you want to do something. It’s called a problem when you want to achieve something. I don’t like that use of the word, I think it’s a very dangerous use of the word. A problem really means that there is a difficulty we want to overcome. But when it is used if we want a new design for a chair, that’s not a problem. So we have a problem with the word “problem.” We have an even bigger problem with the word “creativity.” Huge difficulties with the word “creativ-ity.” And let’s look at three aspects of that. First of all, there are some people who believe that being different for the sake of being different is creative. So if we have doors which are normally rectangular, you say now I want a door that is triangular. It’s different. But unless you can show value, that is not creative. That is what I call “crazytivity” – difference for the sake of being different. That’s one. Then we come to the world of art. And even advertising. And in my sense of the word, artists are not creative. Now, here we run into problems with the word “creative.” Creative means to produce something new that has value. If you make a mess, we can say you have cre-ated a mess, but it doesn’t have much value. So if you produce a new picture, a new sculpture, that’s something new and it has value. But if you use the word “creative” in the way I prefer to use it for change of concept or idea, then we have some artists who were changing their ideas, such as Picasso, who changed his concepts many times, while others – such as Chagall, Mondrian and Braque – they really had the same concept, the same idea, the same type of expression all their lives. They tried different subjects, yes, but there was no change. And if you take an artist and you ask that person to think differently about an existing situation, they are no better than everyone else. So we need to distinguish between creativity that is producing something new of value, which is very useful and a change in the existing concepts, ideas, or ways of doing it. The change factor is important.

L.A.: Where do ideas come from?

Edward de Bono: Well, the fundamental place ideas come from is something I described in a book of mine in 1996 called “The Mechanism of Mind.” In that book, I describe how the brain acts as a self-organizing information system. Self-organizing systems always make patterns. Pattern-making systems are always asymmetric, and creativity comes from that asymmetry. Now that book was read by the leading physicist in the world, Professor Murray Gell-Mann, who got his Nobel Price for discovering the quark, and he read the book and said it’s interesting you were talking about these things ten years before mathematicians started to look at chaos and complexity. He commissioned a group of computer analysts to simulate on computer what I said in the book. And he said, “Yes, it works exactly as you predict.” Another group

in England did the same simulation and said, “Yes, it works exactly as you predict.” So once we understand how the brain forms patterns, why patterns are asymmetric, then we can understand where idea creativity comes from. Now, the reason I use the term “idea creativity” is because that’s what I am talking about … very often with artists, there is aesthetic judgment. Now there is a difference between generating an idea and judging an idea and accepting an idea. Now, in terms of acceptance, you may need some mysterious quality called “aesthetic judgment”. But to produce the idea? No. What is interesting is the fact that the form of art to have shown the most interest in my work is music – even though I am not a musician at all. And here we are looking at both, classical composers and rock composers. The Eurythmics, on their best-selling albums, have always written “Thanks to Edward de Bono.” The same is true with the Pet Shop Boys, Peter Gabriel. It’s because music starts from nothing. In painting, you can paint a portrait, you can paint a landscape and you can paint abstracts, too, of course. But music must start from nothing. So creativity has a very high value. So I guess that’s why music, of all the arts, has been the one most

interested in my work.

L.A.: Yes, I think music … to compose notes, to put them in something that didn’t previously exist on this piece of paper … it fulfils the definition of an idea.

Edward de Bono: But it’s putting them together in such a way, new way, producing a new effect and so on. It’s not representative in the way painting can be representative, or literature can be representative.

L.A.: We were talking about asymmetrical patterns. What exactly goes on in the brain when an idea erupts?

Edward de Bono: Well, if we are going down a normal track and there are sidetracks which you cannot get into from the main track … otherwise life would be impossible, if you had to examine every possible sidetrack … it’s impossible. For instance, one day a fellow got up in the morning and he said: “I’ve eleven pieces of clothing to put on, in how many ways could I get dressed?” A powerful computer, which worked for forty hours non-stop calculated that there are I think 36.860.800 ways of getting dressed. If you tried one every minute, you would need to live 76 years old to try them all. So what the brain does, the dominant track suppresses the others. But if you come in from the other end, you come down that track, join up for the main track. From the other end. When you do that, it’s logical. It’s the same as humor. I’ll give an example: a man of ninety dies, he goes to hell and, as he is wandering around, he sees a friend of his, also aged 90, sitting there with a very beautiful young woman on his knee. So he says to his friend, “Are you sure this is hell? Because you seem to be having a good time.” The friend looks up and says, “Yes, it’s hell, all right, and I am the punishment for her.” Now, absolutely log-ical in hindsight. And that is the essence of humor, that you … once you make that job, the way back is totally logical.

L.A.: Can you elaborate on your lateral thinking, and how it allows people to generate more ideas?

Edward de Bono: Well, there are different points of lateral thinking. There is one strong about the random entry where you put them around the starting point to the random and, as you find your way back to the starting point, that opens up tracks you never have opened up from the centre. Very simple, works very powerfully. Then there’s provocation. Provocation is totally different to our normal habits of thinking. In our normal thinking, every step, every thought, must be logically based on the preceding one. Provocation, no. There may not be a reason for something until after you have said it. And what provocation does, it allows you to jump across patterns instead of going up and down them. Now when I’m talking to mathematicians, they say, “Yes, you are absolutely right.” They say, “In any self-organizing system, provocation is

essential. Otherwise you get stuck in what is called a local equilibrium, and you can never move to a more global equilibrium.” In mathematical terms, provocation is perfectly reasonable and essential. And, in our own real life, we don’t use it because our thinking habits derive from the GG3, that’s the Great Greek Gang of Three, who tell us you must be logical at every step. No, the answer is logical before you use something. When you are at the end and you look back, it has got to be logical, but not how you get there.

L.A.: Are there also other means that are positive for people seeking to generate ideas? Let’s say, Jesus went to the desert, Zarathustra went to the mountains …

Edward de Bono: Of course if you get free of your normal environment, you may escape from your normal way of looking at things. But we can do that without having to go to the desert, with random entry, provocation, challenge, all these ways of doing it. It’s a bit like the traditional idea of a brainstorming. Now, imagine we have someone walking down the road and someone comes along and ties him up with a rope and then someone else produces a violin and we say the person tied up with a rope cannot play the violin. So if we cut the rope, that person is going to become a violinist – that’s rubbish. Similarly, if you are inhibited you cannot be creative – that’s true. If we make you uninhibited, it doesn’t make you creative. It’ll make you a little bit more creative in the sense that any idea you have you will look at more thoroughly. So that’s a very weak approach to the traditional brainstorming and so on.

L.A.: It’s always good to know where the enemy is, who and what is killing ideas?

Edward de Bono: There are people who exist in an organization who are very good at keeping that organization running the way it is. Most managers are in this position for reasons of continuity and problem-solving. Keep doing what you are doing, and if a problem arises you solve it. Now, for them, a new idea is first of all a risk … we don’t know if it’s going to work, then it’s a disruption, then it’s the reallocation of resources, and then it’s a possible failure against your career, so the natural tendency is not to follow new ideas. I’ll give you a really important example: at least in the English language, there is not a word, which says “fully justified venture which, for reasons beyond your control, did not succeed.” Reasons beyond your control might be information you could not have had, might be a political change, and so on and so on. Because we don’t have that word, people are very unwilling to try new ideas because, if they don’t succeed, they are a mistake or a failure. Now, there is a huge need in language for a word, which says “No, that was a fully justified venture. I did not succeed, but it was fully justified.” If we had such a word people would be more willing to try new ideas, but we don’t.

L.A.: What about censorship or selfcensorship – like a petit bourgeois inside us, let’s say.

Edward de Bono: Well, that’s a lack of confidence. Really, once you develop people’s confidence in their creativity, that goes and people have ideas. There is a fellow in South America and he read one of my books and he started teaching my thinking to his workforce. Not just lateral thinking but all the thinking, too. And I saw him again about two months ago and he started teaching my thinking about six years ago. He said, “I used to be half the size of my competitor; today, I’m ten times the size of my competitor.” And ideas from the shop floor … everyone has ideas. And the huge human capital, which is unemployed in organizations because they don’t know how to handle ideas, or encourage or train people to have ideas.

L.A.: What about consensus-seekers and committees?

Edward de Bono: It’s a tricky one, in a sense. If you get a positive and constructive committee, it’s very powerful. If you get a committee where everyone can only exert his or her ego by attacking, attacking, attacking, then that’s very

harmful. And certainly, where I’ve worked with organizations, things have worked when there was someone very senior who became the champion for new ideas. This happened in Newport, that happened in Sanders in Switzerland before they joined up, and so on. And you need that sort of champion to back an idea. Because, otherwise, being exposed to lots of committees, it’s very easy for one committee to say “Why take the risk?” Because the benefit … and if we look at another example, that’s even more serious, the benefit from having a new idea is not proportional to the danger of the risk if it doesn’t work. If we take public service, for example, which really needs lots of new ideas to simplify procedures, it will have a new value. But if you try an idea and it doesn’t succeed, that’s the end of your career.

L.A.: That’s why some people use research as a tool to have some safety. That can be a killer too?

Edward de Bono: This is an interesting point, because people often say to me, “Isn’t it the business of research to have new ideas?” And the answer is no. The mindset of people in research is very often the scientific mindset – how to explore, how to discover, and so on, not how to create new ideas. The thinking in research is not directed toward new ideas, unless they develop from an invention as such. I have often suggested what I call a concept group in an organization. A concept group is not research people, not scientists necessarily, whose business is to look at existing ideas, dying ideas, emerging new ideas, new possibilities of ideas. But research is not necessarily the best place to have new ideas.

L.A.: How can one protect ideas?

Edward de Bono: The best way to protect them from being killed is to have an idea champion in an organization, a senior person who’ll stand behind an idea and really makes sure that it’s properly examined, properly tested, and so on. In consumer product companies, you often have a product champion who stands behind the product, fights for resources, keeps things going when energy is lacking, and so on. So that’s the best way to have a champion who gets behind ideas.

L.A.: Creative people often think it’s enough to just have the idea but I think the idea has to be sold, and selling is hard work. How important is selling?

Edward de Bono: Well, selling is very important and always, as in any selling, you have to sell it in terms of the currency of the receiver and always, if an organization is really interested in cutting costs, you’ve got to have ideas which would help to cut costs, or you’ve got to present your idea that it cuts costs. It’s not much use saying, well, this is a wonderful idea, we need to invest a lot in research and a lot in production facilities. A company that is trying to cut costs may not be motivated to follow that idea. So, just as if you are in a country, you must use the currency of that country; if you are in a certain organization, you must use the currency of acceptance of an idea, whatever it may be.

L.A.: Is there a correlation between ideas and different countries ... ?

Edward de Bono: Some years ago in Japan, they did a survey and they found that, in the 20th century, something like 66% of the new ideas came from the United Kingdom. Only 22% from the United States. Now that is very surprising. Why? Because the United Kingdom in the past used to be a very tightly structured class society. Now what this means if, for example, you are in the top class, you don’t want one of your colleagues to be too clever by half because that shows you up. You certainly don’t want anyone from the other class to be rising through merit. So, theoretically England, should have been very empty of ideas, but there are two points of difference: one is they invented or developed something which shows that they allowed the eccentric. The eccentric was someone who was in the club but not in the club. And if his hair was standing all on end, and he didn’t wash his clothes, so much the better. Then he wasn’t threatening anyone by having ideas. Then, also, there was the ability to be bloody-minded. In England, you don’t tell your colleagues about your idea, and if you do and they don’t like it, they are all bloody stupid and you continue anyway. There is that streak of individuality, bloody-mindedness. That’s the opposite of Japan. In Japan, everyone fits into the structure. However, I do a quite lot of work in Japan. Once the Japanese say we will learn the game of creativity, they say, “Ah so, we are playing this game,” and they can be very creative. And I knew for example the founder of Sony, Masaru Ibuka, and we had long conversations on creativity and this is a point that came out – that the Japanese are very good at playing the game and, if it’s the creative game, will play it, knowing the rules of creativity. But in their natural behavior, no, they don’t wanna have ideas which are different from the group.

L.A.: How important are ideas for the future of a country?

Edward de Bono: Let’s take China as an example: 2.000 years ago, China was very ahead of the West in science and technology. If China had continued the same rate of progress, today China would easily be the dominant part in the world – scientifically, technically, militarily, economically. What happened? What happened was the scholars started to believe that you could move from certainty to certainty to certainty. So they never developed a possibility system. Never developedhypothesis, possibility, speculation. As a result, progress came to a dead end. Now, the same sort of thing is happening in the West today. Because of the excellence of our computers and telecommunications, people are starting to believe that all you have to do is to collect information, and information will make your decisions, information will shape your strategy, and you don’t need ideas – all you need is information. And that is equally dangerous.

L.A.: When the football World Cup came to Germany in 2006, the government and the industrial community launched a campaign called “Germany, the land of ideas.” Can such a campaign help a country boost the spirit to generate more ideas?

Edward de Bono: I would say it’s necessary because … if you look at what’s happening in business, three things are becoming commodities: competence is becoming a commodity, information is becoming a commodity, technology is becoming a commodity. So imagine we have a number of cooks at a cooking competition at a table and each one has the same ingredients, the same stove, cooking facilities … who wins that competition? At a lower level, the chef who produces the highest quality wins. When everyone has the highest quality, the person wins who can take the same ingredients and turn them into superior value, and that requires ideas and creativity. So, in the past, Germany was like the highest quality. Now that everyone has quality, in Japan and China, maybe not today but in five years, they will have as good a quality as everyone. They can hire the best machinery, the best consultancy, the best computer controls, and so on. So creativity is becoming very key. Now, your question is, can a country really make an effort to create an image for an ideas country? The answer is yes, but you have to be serious about it. For example, suppose you said we are going to have a system in Germany where anyone from anywhere in the world who has an idea … we invite him here, we look at the idea. If we think it has value, he can stay here, be totally tax-free, we will organize the patents for him worldwide, and so on and so on. That way, I’m not saying the use of the ideas but the whole image of a country which is taking ideas seriously makes an impact, that’s the point. Because the image most people have of Germany is wonderful quality, excellent quality, but quality is not enough.

L.A.: It is said that in the state between sleep and waking, in that twilight zone, we have more ideas than usual. Why is that?

Edward de Bono: I don’t particularly know. It may be that the brain is active but the parts of the brain which are the sensors are not so active. It could be that we are following patterns which normally we would not follow. It’s rather like having a theory that ADD, attention deficit syndrome, and autism are opposites of the same spectrum. That if you have too much of the inhibitory influence in the brain, you get autism, you are not aware of the world around you, not aware of the people around you. If you get too little, you get an attention deficit disorder; your mind is moving all over the place, you can’t focus, and so on. Maybe in that twilight state, we are moving a little towards that ADD side and therefore we explore more things and have ideas and so on. I suspect this because our normal thinking, which says, “No, that’s not right, that can’t happen,” is reduced.

L.A.: Is that maybe also why some people take drugs, to enhance their ideas?

Edward de Bono: I don’t think that helps too much. I mean, it’s rather like saying you have more ideas if you take alcohol. I don’t think there’s any evidence for that, no. Amphetamines, possibly, but I don’t think alcohol, no. But I don’t think these things are necessary. If we develop and train the ways of thinking to have ideas, we can have lots and lots of ideas. But we have never done that because, ever since the GGT, the Greek Gang of Three, we’ve said everything is logic, and this and this and this, but that’s not how the brain works. See, I wrote a book some years ago about why the human race has never really learned to think. What we have learned is to identify standard situations, provide standard answers. Now, that has done us very well in science, because if you are a scientist dealing with a certain element, the properties are known, constant, permanent. It hasn’t actually been much use in human affairs because people are unpredictable, and if you call someone an idiot he is no longer the same person you called an idiot, there is a loop effect. So our existing thinking, compared with possibilities, is very limited. The human race has never really developed perceptual thinking, design thinking, creative thinking, constructive thinking. We’ve developed judgment thinking, recognition thinking.

L.A.: Could you think of an example where someone had an idea and he had a destination, and the willpower to go through all these minefields of idea-killers on the road, and finally did it?

Edward de Bono: There are many, many possible examples, I mean, a classic one, which is unbelievable, is in medicine. There is a major condition called peptic ulcer, which is stomach ulcer. Hundreds of people, thousands of people, had been doing research on it. Then one doctor in Perth, West Australia, called Barry Marshall said, “Maybe it’s an infection.” Everyone roared with laughter. How could it be an infection? The hydrochloric acid in the stomach could kill any bacteria. No one would listen to him. Thirty years later, it turns out he was right. Now, instead of being on antacids for twenty years or more, instead of having your stomach taken out in a bitter operation, instead of thousands of hospital beds being occupied by people with peptic ulcer, you just take antibiotics for one week and you are cured. Huge effect of an idea. But no one would listen, no one would listen. There were so many people against it, they thought it was a stupid idea and, in the end, he was right.

L.A.: Peter Gabriel once said to me that you could get ideas in the train when you look out of the window and you have this moving of the landscape, and …

Edward de Bono: I think the notion of … if you are distracted, you could probably have more ideas than if you are actually focusing and concentrating … I think many people say something similar when they are playing golf or whether swimming on a river, listening to baroque music, or something. The notion that, if you are distracted, then your mind is more free, whereas if you are concentrated you keep going round and round the same track … Yes, I can believe that. But while those things are true and people describe them in general as a way of producing ideas, they are rather weak.

L.A.: Is there a correlation between spirituality and ideas?

Edward de Bono: If there is, I’m not particularly aware of it. I haven’t made it a particular point of study.

L.A.: Victor Hugo once said you can make a stand against an invasion by an army but you cannot make a stand against the invasion of an idea.

Edward de Bono: Well, yes, I mean that’s looking at extreme cases, because I could say the opposite. I could say, to resist an army you need a thousand men at least; to resist an idea, you may only need one man in the right position and that idea is dead. So, in a way, it’s ideas … sometimes, yes, can move in and you can’t resist it, yes; other times, ideas are very well resisted.

L.A.: But don’t you think really strong ideas tend to come back if they are … ?

Edward de Bono: No, I’m sure there were many ideas in history which were good ideas that … well simply we don’t know why … were killed and died out.

L.A.: Why are you creative?

Edward de Bono: I’ve always been curious about things, how they work, doing them, improving them, and so on. And once you get a certain confidence in the ability to do things and then, in my case, once you think you understand the system, the brain patterns and so on, then it’s an area to work in. You might say, “Why does an artist paint, why does a singer sing?” That’s your activity, and that’s one reason; the other reason is, I think, there are so many areas in the world where we need better ideas. We need better systems of governments, we need better systems of justice, we need better systems of business; all these can be greatly improved. So there is such a huge need for new ideas.

L.A.: So can ideas solve the problems of the world?

Edward de Bono: Yes, in fact, I have an institute I set up in Malta, which is a world center of a new thinking, precisely to provide ideas. I’ll give you an example regarding the conflict in Israel and Palestine and terrorism: The US gives about three billion dollars to the Palestinians, but every time a Palestinian terrorist kills an Israeli civilian they should lose fifty million. Now if you blow up a bus with ten people on board, you’re no longer a great hero. You’ve got to devalue terrorism, you’ve got to devalue it. It’s no use saying, “Terrorism is bad, don’t do it.” You got to devalue it by making it counter-productive.